Today's odd alignment of Barack Obama's second presidential inauguration and the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday is made the odder because by law, the presidential officially was inaugurated on Sunday the 20th and Dr. King was born on the 15th of January, not the 21st. Nevertheless.

The symbolism will not go unremarked, nor should it. Had his life not been ended at 39 and had he been granted the fullness of years, Dr. King would have been 84 last Tuesday. He would have seen, certainly to his great satisfaction, the nation not only elect an African-American president but re-elect him, too.

When Dr. King was murdered on April 4, 1968, Barack Hussein Obama Jr. was 6 years old, a student at a Catholic school in Jakarta, Indonesia. His white Kansan mother had been divorced from his Kenyan father. She had moved to Jakarta with her second husband, an Indonesian.

Mr. Obama would later boast, "I have brothers, sisters, nieces, nephews, uncles and cousins, of every race and every hue, scattered across three continents, and for as long as I live, I will never forget that in no other country on Earth is my story even possible."

He is acutely aware of his place in history, but has attempted to govern not as a "black president," nor even a trans-racial president, but as a post-racial president. He has asked to be judged by the standard of which Dr. King dreamed, not by the color of his skin but by the content of his character.

In another quirk of history, Mr. Obama's second inaugural comes three weeks after the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, issued by his hero and fellow Illinoisan, Abraham Lincoln.

In another post-racial quirk, if the blood of slaves flows in Mr. Obama's veins, it comes from his white mother's family. Genealogical experts suggested last year that one of Ann Dunham's forebears was a slave in 17th century Virginia named John Punch.

Whatever his ancestry, the president knows that the stain of slavery is not gone in 21st century America. In Philadelphia, as a candidate for president in March 2008, he gave the finest speech of his life, outlining his views on race in response to criticism leveled against the inflammatory language of his Chicago pastor, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright:

"William Faulkner once wrote, 'The past isn't dead and buried. In fact, it isn't even past.' We do not need to recite here the history of racial injustice in this country. But we do need to remind ourselves that so many of the disparities that exist in the African-American community today can be directly traced to inequalities passed on from an earlier generation that suffered under the brutal legacy of slavery and Jim Crow."

Dr. King consistently preached the same theme. Five days before his death, at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., he said, "In 1863 the Negro was told that he was free as a result of the Emancipation Proclamation being signed by Abraham Lincoln. But he was not given any land to make that freedom meaningful."

At roughly the same time, the lands were opened in the West for white settlers and land-grant universities were created to teach them to farm. Slavery was only the beginning of the injustice.

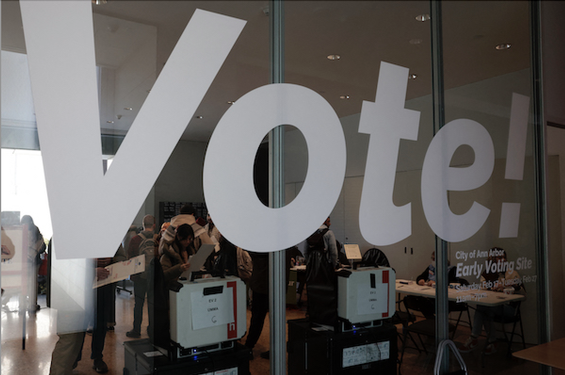

Injustice has been addressed but not erased. A black man is president, but look at the color of the men in our prisons and jails and the color of the children in our worst schools. Consider that after this year, the U.S. Supreme Court will consider a challenge to the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

All inaugural speeches, particularly second ones, are compared to the impossible standard set by President Lincoln in the month before his death, five days after Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. Thanks to Steven Spielberg and Daniel Day-Lewis, Americans now have easy access to vivid, albeit slightly historically skewed, images of these events.

In 700 perfect words, President Lincoln traced the origins of the war, the moral case against slavery, the uncertain will of God and the case for binding up the nation's wounds with "malice toward none, with charity for all."

Had he, not Andrew Johnson, been president during Reconstruction, the nation surely would have made a better peace. It might have more generously extended its blessings to all. That job was left to succeeding generations. We have done an imperfect job with it.

We can't expect Mr. Obama's speech today to reach Lincolnian heights. But we hope he will summon the nation to the kind of justice for all that Lincoln, and Dr. King, sought.

In his second inaugural, Lincoln laid bare the lie that the war was being fought for any kind of noble cause. Slavery was not only a moral issue, but an economic one; historians reckon that in 1860, at the New Orleans slave market, a prime field hand was worth roughly what a Mercedes-Benz sells for today.

"All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war," Lincoln said, a simple verity that in some places in the South is still not accepted.

Martin Luther King Jr. crusaded not just for racial justice, but for economic justice. "I say very honestly that I never intend to become adjusted to segregation and discrimination," he said at Western Michigan University in December 1963. "I never intend to become adjusted to religious bigotry. I never intend to adjust myself to economic conditions that will take necessities from the many to give luxuries to the few."

Economic injustice is the great issue our time, too, manifest in income equality, health care inequality and educational inequality. Mr. Obama must address it, if not in his speech today, throughout the next four years.

Yes, there are powerful political and economic interests mounted against him. Yes, the president prefers to be a conciliator and consensus-builder. But as Dr. King said in his speech at the National Cathedral, "Ultimately a genuine leader is not a searcher for consensus, but a molder of consensus."

(c)2013 St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Distributed by MCT Information Services