In “Drive My Car,” a lovely movie about the interior dramas we all carry around through life, a multilingual group of actors have come to Hiroshima to prepare a production of Anton Chekhov’s 1898 play “Uncle Vanya.” The director, an emotionally isolated widower and former actor played by Hidetoshi Nishijima, sees his task as one of steering his company away from conspicuous, effortful acting — the familiar performance habits, that is, often blocking a performer’s way to a truer, easier place of emotional expression.

“It was hard work, and we had to dig deeply into our hearts,” as actor Olga Knipper (later Chekhov’s wife) said of the 1898 Moscow premiere of “Uncle Vanya.”

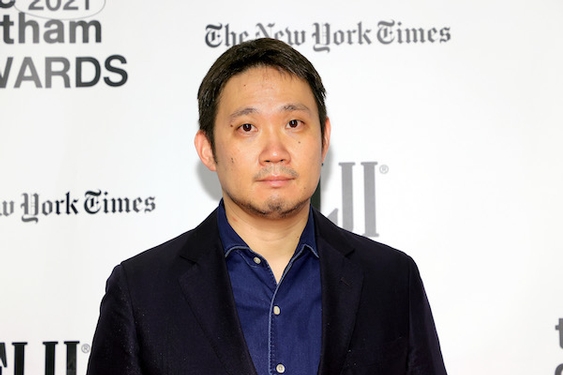

One of the great strengths of “Drive My Car” is the way co-writer and director Ryusuke Hamaguchi revisits the dangerously familiar theme of art informing life, and vice versa. Chekhov admirers may argue with various aspects of the “Uncle Vanya” we see in rehearsal here. For one thing, there’s not a speck of humor in what Chekhov himself classified as a comedy. This may be a matter of the Japanese language translations of Chekhov; it took literally generations of English-language translations for the first truly witty ones to arrive, thanks to Michael Frayn, Tom Stoppard, David Mamet and others.

Theater critics are really only guessing about what works, and why, for the first few years of their writing lives. (Some never learn.) When I was starting out, Chekhov was beautiful in theory, a frustrating riddle in practice. Now and then, you’d find a moment of mysterious connection between two actors, and between the actors and the characters. And then you’d go three, four, 10 Chekhov productions before that connection happened again.

Decades earlier the Gershwin brothers wrote “But Not For Me” for the 1930 musical comedy “Girl Crazy.” One Ira Gershwin lyric lamented: “With love to lead the way/ I’ve found more clouds of gray/ Than any Russian play could guarantee.” Punchline! Chekhov had only been dead 26 years, and already, in America, he was a punchline, a code word for misery. Was that really all there was to this giant? Whining, plus desolation?

Then I saw one that worked: a 1984 Williamstown Theatre Festival “Uncle Vanya” with Austin Pendleton, Edward Herrmann, Blythe Danner and Dianne Wiest. Funny. Romantic. Relatively straightforward staging — the play is simply “scenes from country life,” according to Chekhov — but the actors revealed that unless the behavior, circumstances and painful, comic, tragic yearning of Chekhov’s characters is amusing first, the profound human sadness cannot sneak up on you later.

Back in 2004, for the Tribune, I sat down with cast members of two Chekhov productions (a “Cherry Orchard” and a “Seagull,” at Steppenwolf Theatre and Writers Theatre, respectively) and learned a lot about their work on this revered, misunderstood playwright. If you see “Drive My Car,” which you should, you might be curious about the writer everyone’s wrestling with in rehearsal, and in spirit, as they go about their lives.

The following is a revised version of that roundtable discussion, with insights provided by, among others, the splendid Amy Morton of Steppenwolf and “Chicago P.D.” renown.

—When was Anton Chekhov born? Jan. 16, 1860, in the seaport of Taganrog, Ukraine. He was the son of a brutish merchant and grandson of a serf who had bought his freedom 19 years earlier.

—Why is Chekhov considered the crucial modern playwright? From the Cambridge Guide to the Theatre: “By fragmenting the well made play, scattering exposition throughout, compressing, internalizing and excising action, Chekhov created the ‘theater of mood,’ of misdirection, non-eventfulness and partially stated meaning.”

—Another answer, from Yasen Peyankov, who played Lopakhin in the 2004 Steppenwolf staging of “The Cherry Orchard”: “I think Chekhov is the beginning of modern theater. The reason ‘Seagull’ failed in 1896 is that it was performed in the old way, where actors were facing the audience and declaiming their lines. And here was this new voice in the theater that required a completely different style of acting. When the Moscow Art Theatre came to America in the 1920s with the productions of Konstantin Stanislavsky, many of the actors ended up staying here. They were largely responsible for the Group Theatre, the Actors Studio, everything that leads to (Marlon) Brando and (Robert) De Niro … It all starts from that tour.”

—Chekhov and Stanislavsky didn’t see eye-to-eye. Chekhov thought his plays (except for “Three Sisters”) were comedies; Stanislavsky considered them much heavier, more tragic affairs, albeit a new kind of drama requiring a more fluid, less bombastic acting approach.

—What’s it like for an actor to inhabit a Chekhovian universe eight times a week? Susan Hart, who portrayed Arkadina in the 2004 Writers Theatre “Seagull”: “I did Michael Frayn’s ‘Benefactors,’ playing a woman who absolutely showed no emotion at all, and I’d find myself bursting into tears in the car because I had so much penned up inside me. With (Chekhov) the opposite happens: I leave it all on the stage. What Arkadina says is at the expense of everyone around her, and it makes a big difference in terms of the way I feel when I walk out the door. The woman’s insensitivity is astounding. She just devastates anyone in her path, so there’s great fun in that.”

—On the other hand … Amy Morton, who played “Lovey” Ranevskaya in the 2004 Steppenwolf “Cherry Orchard”: “For me it’s the complete opposite. Lovey feels everything. There isn’t a moment where she’s not feeling and empathetic to somebody, or some situation. And it’s a woman who starts the play in a place of extreme loss — son, husband, lover — and it only gets worse. So frankly, every night, I’m a little devastated. Go home. Stay in bed for most of the day. And then go, ‘OK, gotta do it again.’ I haven’t done a role this emotionally difficult in, I don’t know … It’s just terrible. And then, you know, you have to put on a corset.”

—A director’s perspective: Michael Halberstam, director of the 2004 “Seagull”: “American actors tend to look for a character arc, a story arc, and I think there is no arc in ‘Seagull,’ it’s more like a series of circles. I think we attempt to connect, and these people profoundly don’t connect. And we also tend to see our characters in the best possible light. And the minute you start doing that with Chekhov, you completely lose the spectacular intricacy of neuroses.”

—Translator Curt Columbus’s perspective: “In rehearsal you get to a place where you’re going, why is this elusive? Why is this just outside of my grasp? We went through it with ‘Cherry Orchard,’ where director Tina Landau and I said to each other: ‘Well, it’s a Chekhov play right now.’ Which we meant in a bad way, not the thing that we wanted. I remember watching a run-through on a Friday night and thinking: ‘That’s it! That’s the one.’ And then it didn’t come back for, like, four performances. What changed? I don’t know. No one knew.”

—Amy Morton: “One of the problems is, you can’t muscle it. You can’t depend on your chops to get you through it. Chekhov is like wearing Saran Wrap: The minute you lie, people see right through it. You can never go (smug actor voice), ‘You know that thing I did last night? I’m gonna do that again. That worked so well.’”

—Chekhov’s fellow Russian, Maxim Gorky, said this after Chekhov’s death: “It seems to me that all those who found themselves in his company inevitably felt the desire to be simpler, more honest, more themselves.”

—When did Chekhov die? July 15, 1904, of tuberculosis. He spent his final days at a spa in Badenweiler, Germany. From Olga Knipper-Chekhov’s memoirs: “The doctor arrived and ordered Champagne. Anton Pavlovich sat up and loudly informed the doctor in German (he spoke very little German), Ich sterbe’ (’I am dying’). He then took a glass, turned his face toward me, smiled his amazing smile and said, ‘It’s a long time since I drank Champagne,’ calmly drained his glass, lay down quietly on his left side, and shortly afterward fell silent forever.”

—And then? From Knipper-Chekhov, who lived to the age of 90: “Then two other things happened. The dreadful silence of the night was disturbed only by a huge black moth which burst into the room like a whirlwind, beat tormentedly against the burning electric lamps, and flew confusedly around the room. The doctor left, and in the silence and heat of the night, the cork suddenly jumped out of the unfinished bottle of Champagne with a terrifying bang.”

———

©2021 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.