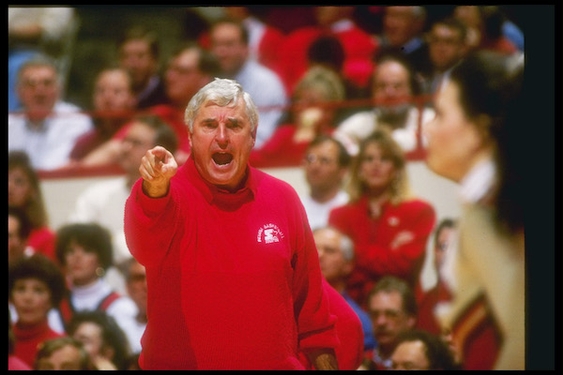

Bobby Knight, the combustible college basketball coach who bellowed and cursed at referees, fans and even his own players but came to be regarded as a mastermind of the game as he guided the Indiana Hoosiers to three national titles, has died at his home in Bloomington, Ind., surrounded by his family.

Both loved and loathed, Knight died Wednesday, the Knight family announced via his website. He was 83.

Long recognized as one of basketball’s greatest coaches, Knight was forever remembered for cursing, gesturing wildly, berating officials and finally throwing his chair onto the court as the opposing team was about to shoot free throws. To much of the world, sporting or otherwise, he became “the crazy coach who threw the chair.”

And yet, that was only one of a multitude of incidents in the contradictory life of a man who demanded impeccable behavior and judgment in others but whose own startling lack of self-control often overshadowed his coaching genius.

Among the more notable:

In a game against Kentucky, after a tirade against the officiating crew, Knight bopped Kentucky Coach Joe B. Hall on the back of his neck with an open palm. And Hall was a fishing buddy of Knight’s.

During the 1979 Pan-Am Games in Puerto Rico, he was accused of assaulting a policeman, calling him the N-word, calling the Brazilian women’s team “dirty whores,” and saying Puerto Rico was good only for “growing bananas.” Both he and others present denied the accusations but, in absentia (he’d already left the commonwealth) he was found guilty of assault and sentenced to six months in jail. He never returned to serve his time and, years later, the conviction was reversed.

He fired a race starter’s pistol, loaded with blanks, at a Louisville sportswriter.

During the Final Four of the 1981 NCAA tournament in Philadelphia, he grabbed a heckling Louisiana State fan and stuffed him into a trash can.

Irked after being charged with a technical foul in a game against Illinois, he kicked a megaphone, then yelled at Indiana cheerleaders to shut up so future UCLA coach Steve Alford could shoot a free throw.

In an interview with Connie Chung on national television, he made a crude and ill-advised analogy involving rape, remarks he later said were misinterpreted.

Using a bullwhip, he gave a mock beating to Calbert Cheaney, one of his Black players, then later insisted the incident was not racially motivated.

He head-butted player Sherron Wilkerson after pulling him out of a game, then later claimed the action was unintentional.

He was accused of choking a restaurant patron, who said Knight had been making racist remarks.

He was accused, years after the alleged incidents, of choking player Neil Reed during practice — Knight denied it but a former assistant coach came forward with a video — and of throwing a vase at an IU secretary, breaking a picture behind her desk.

And yet, Knight won 902 games as a head coach over 42 seasons at Army, Indiana and Texas Tech, losing 371 for a remarkable .709 winning percentage.

In 29 seasons at Indiana, where he fine-tuned the motion offense introduced by Hank Iba at Oklahoma State, insisted on tenacious defense and discipline, discipline, discipline, his Hoosiers won 662 games while losing 239, an even more remarkable .735 percentage. There were 22 seasons of 20 victories or more and his 1975-76 team went unbeaten, winning the first of three national championships for Indiana under Knight’s watch.

In NCAA tournament play, Knight’s Hoosiers were 42-21. Besides winning the three championships, Indiana lost twice in the semifinals. There was a National Invitation Tournament championship, back in the days when that was worth bragging about, as well as a runner-up finish in the NIT.

Indiana under Knight won 11 Big Ten Conference titles. He was national coach of the year four times, Big Ten coach of the year eight times.

In 1984, he coached the U.S team to a gold medal in the Los Angeles Olympics, having previously led a U.S. team to the title in the 1979 Pan-Am Games.

At Texas Tech, where he landed after Indiana had fired him, he quickly turned a sinking program beset with recruiting violations and the subsequent loss of scholarships into a consistent winner, getting the Red Raiders into the NCAA tournament three times.

Many who played for him went on to successful professional careers, and many more went on to successful coaching careers, most notably Duke’s Mike Krzyzewski, who played for Knight at West Point and ultimately surpassed him in coaching victories.

Perhaps most impressive, in a sport notorious for recruiting violations and other shenanigans, Knight ran a clean program. More than 90% of his players graduated, none of his teams drew NCAA sanctions for infractions, and he campaigned tirelessly and loudly for reforms in college basketball, at one point offering to identify cheating coaches to the NCAA.

The late Pete Newell, a revered former coach and among basketball’s most influential figures, once observed in Sports Illustrated, “What Knight does do is the single most important thing in coaching: He turns out educated kids who are ready for society.”

But, of course, he did it his way, mingling gestures of compassion and charity with the kind of behavior commonly associated with a 5-year-old. Casting himself as a teacher, he often was more bully than counselor, more screamer than lecturer, more heavy-handed disciplinarian than instructor.

For all of his bluster, Knight saw himself in simple terms. “I just love the game of basketball,” he said. “The game! I don’t need the 18,000 people and all the peripheral things. To me, what’s most enjoyable is the practice and preparation.”

Most of his players held him in high regard. Alford, who was UCLA coach from 2013-2018, alternated as star point guard and object of Knight’s ire at Indiana. He considered Knight “the greatest coach ever,” and once said, “He made me a better man, and for that I’m grateful.”

Isiah Thomas, another Indiana star who went on to NBA greatness, got a good taste of Knight even before playing for the Hoosiers. He was 18 and had yet to begin his freshman season at Indiana when Knight chewed him out publicly in loud and colorful language for mental mistakes with the U.S. team in the Pan-Am Games.

When observers sided with Thomas, he said, “I deserved it,” and calmly explained that one of the main reasons he’d chosen Indiana was that Knight demanded the best from his players.

And there remains a significant segment of Indiana’s hoops-crazy population that considers Knight one of the best things ever to hit the Hoosier state.

For some, though, Knight was an acquired taste.

Larry Bird, as good a player as the state of Indiana ever produced, but a shy and lonely freshman when he began his college career at Indiana, quickly realized he and Knight would never be a good mix and transferred to Indiana State, where he had a stellar career before moving on to an even more stellar career with the Boston Celtics.

In his book, “When March Went Mad: The Game That Transformed Basketball,” Seth Davis quotes Knight as saying: “Larry Bird is one of my great mistakes. I was negligent in realizing what Bird needed at that time in his life.”

Still, for all of his shortcomings, Knight had a softer side. Although he carried on a running feud with Sports Illustrated and delighted in denigrating sportswriters — “Most of us learn to write in second grade and then go on to other things” — he made lavish contributions to and spearheaded fundraising for university libraries at Indiana and Texas Tech.

If he drove his players hard when they were with him, he also was there for them if later in life they fell on hard times, helping out with job possibilities, financial assistance or simply moral support. For Landon Turner, there was nobody greater.

Turner was one of Knight’s projects, a gifted player who wasn’t getting Knight’s message. Then, midway through his junior season, the light went on and he became the player Knight had hoped to see. With Turner and Thomas leading the way, Indiana stormed through the 1981 NCAA tournament, beating North Carolina for the championship. Big things were expected of Turner as a senior.

That summer, though, he suffered a spinal fracture in a car accident and was paralyzed from the waist down. Knight cut short a Montana fishing vacation so he could be there when Turner came out of a coma five days later, then was instrumental in the young man’s recovery. He donated a reported $60,000 of his own money, then led a statewide campaign that raised more than $500,000 to help with Turner’s hospital expenses, keeping the project going long after Turner had resumed his life.

He also persuaded Indiana to let Turner, who used a wheelchair following the accident, stay on scholarship and made him captain of the 1981-82 team. After one disappointing loss, Turner said, “Coach, you should have called my name. I would have gotten up.” Knight replied, “Landon, I’m saving you for the next game.”

Robert Montgomery Knight was born Oct. 25, 1940, in Massillon, Ohio, and grew up in nearby Orrville, where he played high school sports, starring on the basketball team. He went on to Ohio State — coach Fred Taylor referred to him as “the brat from Orrville” — playing as a reserve on the 1960 NCAA championship team that starred future Hall of Famers John Havlicek and Jerry Lucas. The Buckeyes beat Newell’s California team in that year’s final, then lost to Cincinnati in the final each of the next two seasons.

Still, Knight had his on-court moments. In the 1961 title game, for instance, he came off the bench with 1:41 to play and Cincinnati leading 61-59.

Recalled then-assistant coach Frank Truitt: “Knight got the ball in the left frontcourt and faked a drive into the middle. Then he crossed over [his dribble] like he worked on it all his life and drove right in and laid it up. That tied the game for us and Knight ran clear across the court like a 100-yard dash sprinter and ran right at me and said, ‘See there, Coach, I should have been in the game a long time ago.’ “

Truitt’s response? “Sit down, you hot dog. You’re lucky you’re even on the floor.”

Knight graduated in 1962 and, after a year as a high school assistant coach, joined the Army, a requirement for taking an assistant’s job at the U.S. Military Academy where, two years later, at 24, he became the youngest head coach in major men’s college basketball.

He was only a private but quickly became known as “the General,” or, in honor of World War II Gen. George S. Patton, one of his heroes, “Gen. Patton.”

In his six seasons at Army, hardly a basketball powerhouse, the Cadets won 102 games and Knight was quickly identified as a can’t-miss young coach, which he quickly proved at Indiana.

That he remained there as long as he did, what with his antics drawing as much attention as his hard-playing teams, puzzled many. But winning covers a multitude of sins among die-hard fans, and Knight was seen largely as a rebel-hero, one not at all reluctant to speak his mind, with just the right amount of rogue in him.

His chair toss, for instance, during a home game against Purdue late in the 1985 season, drew an eruption of cheers that only grew louder when he was thrown out of the game.

When it all ended, of course, it ended in turmoil. Myles Brand had moved into the president’s chair at Indiana and warned Knight several times to tone things down, finally announcing that the coach was on a “zero tolerance” policy after Knight had largely ignored him.

In September of 2000, Knight crossed paths on campus with a freshman student, Kent Harvey, who greeted him with, “Hey, Knight, what’s up?” Knight grabbed Harvey by the arm and lectured him on proper respect, insisting that Harvey should have addressed him as “Mr. Knight” or “Coach Knight.”

Enough was finally enough for Brand, who asked Knight to resign. Knight refused and, amid great controversy, was fired. Knight took his case to his players and later to the Indiana students, claiming he had been treated unfairly.

Students, in turn, marched on Brand’s residence and burned him in effigy. Brand and his wife, Peg, received death threats and finally moved out of their campus house until things calmed down.

In an interview years later, Knight was asked about Brand and the other administrators who pushed for his ouster. “I hope they’re all dead,” Knight said.

After being run out of Indiana, and amid strong opposition by some faculty, Knight was hired by Texas Tech in 2001. His term in Lubbock was relatively calm compared to his Indiana days, although never entirely so, and on Feb. 4, 2008, with the season still in progress, he announced his retirement from coaching, turning the team over to his son Pat.

A five-year run as a TV analyst for ESPN ended in 2013 after announcer Rece Davis had to explain to him the difference between the shot clock and the game clock during a game at Vanderbilt. Several years later, the FBI and U.S. Army investigated complaints from four women who said Knight groped them or touched them inappropriately during a visit to a U.S. spy agency in 2015. The investigation concluded without charges being filed.

In 2020, Knight returned to IU’s Assembly Hall for the first time since his firing, walking onto the court as fans roared with approval and chanted his name. The former coach appeared to grow misty-eyed.

Knight is survived by his second wife, Karen, and sons Tim and Pat from his first marriage, which ended in divorce.

In typical Knight fashion, he left a specific after-life plan: “When my time on Earth is gone, and my activities here are passed, I want them to bury me upside down, and my critics can kiss my ass.”

Kupper is a former Times staff writer.

Staff writer Steve Marble contributed to this report.

©2023 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.