One of the greatest of these cynical and often cinematically beautiful movies, The Third Man, remains both relevant and riveting almost 50 years after its release in 1949. The picture takes place in Vienna after the war and follows Holly Martins (Joseph Cotton) as he attempts to track down a murdered friend – played by Orson Welles.

The shadows and light in the film serve as a metaphor for the story, which bristles with deception and mystery. Cotton finds himself turning into a detective as he attempts to uncover the facts, but the more he uncovers, the more corrupt everything seems.

The sort of naïve American that Cotton plays, attempting to “do good” yet bumbling along like a blind man, feels especially relevant right now as the U.S. stumbles along in the midst of a new war, equally ineffectually. The “aw shucks” quality of the American temperament looks increasingly absurd and even surreal played against the stark reality of the situations in these war torn foreign countries. What was once genial now looks plain stupid.

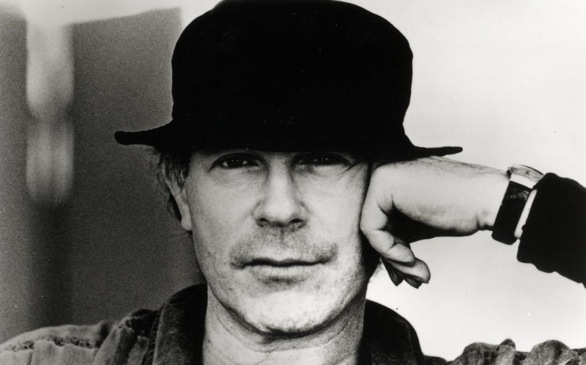

Written by Graham Greene and directed by Carol Reed, The Third Man represents what made American films great with excellent all-around attention to detail and intelligent follow through. The film offers up the fantastic possibilities of the medium in a way that makes many of today’s offerings feel sorely lacking.

Also recently released is Steven Soderbergh’s The Good German (coincidentally, he provides commentary on The Third Man). Not noir exactly but maybe neo-noir, the picture owes much to The Third Man and also Casablanca.

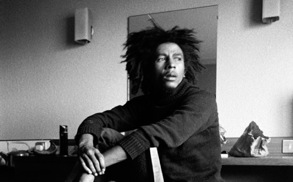

Set in post-war Berlin, Soderbergh’s take on noir follows an American Army war correspondent played by the only actor conceivable for this role, George Clooney. Clooney inhabits the role of Jake Geisner with an almost eerie, out-of-time presence that doesn’t seem silly or tired – what could have felt like a tired facsimile of a used Cary Grant part.

Unfortunately, Cate Blanchett, whom I usually adore, does not fare as well in the guise of Lena Brandt, a German woman willing to do anything to get out. The period conceit sits like a suit of armor on Blanchett’s shoulders, weighing Lena down so that it’s a wonder she can even lift her head.

Tobey Maguire, as Tully, a corrupt American soldier, also fails to lift the material beyond hollow homage. It is as if everyone from the writer Paul Attansio (adapting the novel by Joseph Kanon) to Soderbergh to the cinematographer, Peter Andrews, felt trapped by the conventions of noir so they got stuck in a sort of film school exercise rather than a place to launch from.

Other films, like Brick, have done a much better job at taking the spirit of noir and twisting it into a more modern creation. There is so much in modern life that can be captured by the tone of noir – the seedy, corrupt, dark side of life – I’m not sure why a filmmaker would be driven to essentially retread a great movie like Casablanca. Soderbergh of all people should know this, as he has the ability to make a film like The Limey, which showcases neo-noir at its best.

The Good German: C

The Third Man: A

Extras: intro by Peter Bogdanovich, commentaries by Steven Soderbergh and Tony Gilroy, “making-of,” Austrian documentary featuring interviews with cast and crew, radio clips, behind-the-scenes photos, archival footage of postwar Vienna, a booklet featuring essays by Luc Sante, Charles Drazin and Philip Kerr, web-exclusive essay on Anton Karas by musician John Doe.

The Third Man and The Good German are both currently available.