Model turned actress. Actor turned rock star. Writer turned director.

In Hollywood, there are always people looking to add a new creative title to their resume, loading up on the hyphens until they’re a writer-director-producer-actor-designer-dog walker, often ignoring that focus can be a good thing.

Dennis Hopper, who passed away on May 29 from complications of prostate cancer, was an easy riding misfit best known for playing drug-addled crazies and putting his Method training to good use on screen. But he was also a prolific painter, photographer, sculpture, video and mixed media artist.

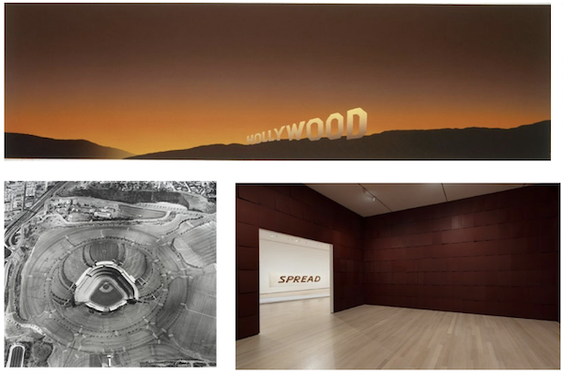

His posthumous show, Dennis Hopper Double Standard, the first comprehensive exhibit of his work, opened last month at the Geffen Contemporary, the Museum of Contemporary Art’s satellite space in Little Tokyo, and, like the actor who created the work, it’s an overwhelming spectacle that’s not always coherent.

Take, for example, the mammoth statues that greet you as you enter the show. Flanking either side of the warehouse space are towering replicas of the La Salsa Man and the Mobil Gas Man, huge two-story-tall enamel and fiberglass figures made using molds of old commercial signs, of a cartoonish Mexican food server – complete with sombrero – and Mobil gas attendant. Between the two stands an unsettlingly lifelike sculpture of Hopper as a stoic grayscale cowboy frozen in a color desert. In the midst of the pop art landscape, his self-portrait is textured and tangible, soul oozing from the eyes, but it’s a disjointed combination that sets the tone for the rest of the show.

Moving into the gallery, the first thing that strikes you is the vastness of the collection. Hopper worked on his art for over six decades, beginning as a painter in the late 1950s focused on abstract expressionism and moving into photography, graffiti, video installations and more.

The problem is despite cultivating numerous styles, none of them feel like his own. Each piece of art (which were all chosen and organized by painter, movie director and cultural impresario Julian Schnabel with help from L.A. art dealer Fred Hoffman and New York art dealer Tony Shafrazi) acts as a time capsule, reflecting the most successful artists of the day. During the ’60s, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol are heavily present in Hopper’s work, but by the ’80s, he’s moved on to “borrowing” from Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. Rather than witnessing an evolution, each new decade seems to reboot Hopper’s work, giving the feeling that he’s starting from scratch rather than developing as an artist.

Perhaps his least impressive period was the late-1980s into the ’90s. Obviously affected by the Rodney King riots and perhaps one too many viewings of his film Colors, Hopper’s art takes on the look of artificial graffiti, streaked and spray painted on canvases with gesso-ed surfaces meant to mimic stucco or scrawled over chain link fences that bring to mind stage sets. Rather than feeling raw and urban, they’re uncomfortably amateur, the sophomoric work of someone striving for meaning.

The show’s greatest weakness is its attempt at creating a full retrospective. Certain eras of Hopper’s work need not be viewed by the general public. Had the show focused exclusively on his photography, it would have been a soaring triumph, a fact that smacks you on the noggin the moment you step into the show’s centerpiece, a room brimming with over 200 captivating, vibrant black-and-white photographs shot throughout the 1960s.

Hopper is at his worst when aping other visual artists of the time and at his best when behind the camera, documenting the swirling world he existed in. Photos of Warhol hiding behind a silver flower, Ike and Tina Turner frolicking in Hopper’s home, Jane Fonda practicing archery in a bikini on the beach in Malibu or Bill Cosby selling star maps on Sunset Boulevard hint at Hopper’s incredible photographic potential.

While the art may be lacking, you can always slip into the backroom where they’ve compiled video clips from films such as Easy Rider, True Romance, Giant and Apocalypse Now and take a moment to appreciate Hopper’s truest art and lasting legacy: the one he left on celluloid.

Geffen Contemporary at MOCA is located at 152 N. Central Ave., Los Angeles. For more information, visit moca.org.

Culture: Art

Dennis Hopper Double Standard: Now-Sept. 26 @ Geffen Contemporary at MOCA

By Sasha Perl-Raver

Article posted on 8/25/2010

This article has been viewed 3611 times.