In January 1994, the state of Texas celebrated the Dallas Cowboys’ second consecutive NFC Championship win, assuring them a spot in Super Bowl XXVII. As the city of Dallas embraced the victory, Cowboys’ star quarterback Troy Aikman was in the hospital unable to remember anything that had happened.

Aikman suffered a traumatic head concussion in the third quarter of the NFC championship game against the San Francisco 49ers. Hours after the game, he sat in a pitch-black room in the hospital. Super agent Leigh Steinberg was one of the few visitors he had that night.

“Troy looks at me and says, ‘What am I doing here? Did I play today? Did I play well?’ I said, ‘You’re going to the Super Bowl.’ His face brightened, and he got very excited,” Steinberg says. “Five minutes passed, and he looked at me blankly, asked the same sequence of questions all over again.”

Steinberg says he first realized the importance of head concussions after seeing the shape that his star quarterback was in.

“It terrified me to see how tender the bond was between sentient consciousness and dementia,” he says. “I could no longer represent players in the NFL unless I took the concussion issue seriously and got information from players about longterm repercussions.”

The NFL recently began addressing the issue of head concussions in athletes. The league began fining players during the 2010-2011 season for head-to-head collisions during games. The new rule implications came about thanks to the long struggle of Steinberg who advocated the seriousness of this issue.

He has been representing athletes since 1976, NFL players such as Troy Aikman, Steve Young, Warren Moon and Ben Roethlisberger.

Steinberg says that during the late 1980s and early 1990s, NFL quarterbacks such as Steve Young and Troy Aikman were suffering multiple concussions during the 16-week NFL season. He came to find out that no doctor had any idea what were the longterm consequences of concussions or ‘how many is too many?’

“Steve Young suffered a concussion in a game against the Cardinals but denied it happened. He went into the following week’s game as if nothing had occurred,” Steinberg says. “He had impaired reflexes and higher risk for a second concussion. He received a blow to the head and never played again.”

That prompted Steinberg to begin to hold Concussion and Player Safety Conferences throughout the 1990s in Newport Beach, Calif. He invited leading neurologists to make presentations about the short and longterm effects of concussions on athletes.

“If you see the shape these former players are in, it defies conscience not to help them,” Steinberg says. “It’s one thing not being able to bend over for your child at age 50 … it’s another thing to not be able to recognize your child.”

There are an estimated 1.6 million to 3.8 million sports concussions a year, according to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Sports concussions are traumatic head injuries that can happen from both mild and severe blows to the head, and can cause the brain to swell. Symptoms include dizziness, nausea, memory loss and headache.

“There are a number of patients that also have emotional and behavioral changes such as impulses and changes of judgment,” says David Ko, MD, professor of neurology at USC. “Recently there’s been a few cases of people in football particularly, who have unfortunately taken their lives.”

A study by the University of North Carolina’s Health Center found that clinical depression and suicide among retired NFL players was correlated with the amount of concussions they had received throughout their careers. Some doctors believe that three or more concussions trigger higher risks of athletes developing Alzheimer’s or dementia. USC was selected by the NFL to be one of the sites where neurologists can evaluate the brain function of former NFL players, whose current average lifespan is 55. No wonder people say that NFL stands for ‘Not For Long’.

“One has to realize you can’t be a football player forever,” says Willie Gault, former Chicago Bears player.

After car accidents, sports-related concussions are the second most common cause of traumatic brain injury. Neurologists say once an athlete suffers a concussion, they are as much as four times more likely to sustain a second one.

“We are still trying to decide what the right test is. Do we pull him out as soon as it happens? How long does it take to recover? When can he play? [These are] all common questions when it comes to concussions in games,” says Michael Crovetti, an Orthopedic Surgeon.

Steinberg advocated ideas to the NFL about having neurologists on the sideline, pulling AstroTurf out of stadiums, outlawing blocking and tackling with the head in games, establishing an accepted methodology of diagnosis and treatment, rating the severity of concussions and forbidding reentry into a game or two, or a season.

After two conferences in Newport Beach and dozens of speeches and interviews campaigning on the issue, not much had changed. In 2007, Steinberg and Warren Moon, a former NFL quarterback, and Dr. Tony Strickland of the Concussion Institute for Los Angeles hosted another seminar. In order to grab the world’s attention, Steinberg invited the national press, AP, CNN, the New York Times, Washington Post, ESPN and the Los Angeles Times.

“I brought [them] to insure that the results were widely disseminated and that the NFL could not ignore the urgency of the problem. I called it a ‘ticking time bomb’ and ‘undiagnosed health epidemic’,” Steinberg says, “[This] led to Commissioner Roger Goodell convening a NFL Physician’s Conference to examine the problem, [and] the denial which existed surrounding the issue started to fall.”

After his stunt, the NFL issued a “whistleblower’s edict” urging NFL athletes to report players whom they thought were impaired and to generally look out for each other. They began to use the Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Test (IMPAACT), which is a baseline test that established the normal functioning of a player’s brain. This could be used to judge the degree of impairment in an injured player.

Steinberg later organized a second conference in 2009 campaigning for it, and both conferences received national attention.

Although it’s alarming that this issue has been concealed for so long, what’s most disturbing is that most fans think that by giving players fines for head-to-head collisions is hurting the game of football.

“It’s making it weak, you might as well play tag football,” says Dennys Hernandez, a long time Denver Bronco fan, “we watch to see those hard hits, and now it’s watered down, we might as well not watch it.”

Steinberg as well as other former players joined together to address this epidemic, and show people the seriousness of it since it seems no one cares about the players once they step off the field.

“I’m glad they’re taking those kinds of precautions … but it definitely changed the perception of QBs even more,” says Mark Sanchez, current quarterback for the New York Jets. “You’re already [seen as] the prima-donna, the china doll out there … it’s sad and almost embarrassing.”

The NFL head-to-head collision rule fines defensive players for tackling, or going for a hit leading with their helmet. Although it’s a split second decision for a player to hit another with his helmet or shoulder, players can be fined up to $75,000. They can also face possible suspension depending on the severity of the hit, according to NFL.com. Yet this rule is controversial because of the inconsistency of officiating.

“With the hits too, it’s a tough call there’s definitely unnecessary hits out there,” says Matt Leinart, current quarterback for the Houston Texans. “I have to say I agree with some [calls], and I don’t agree with some.”

Steinberg continues pushing this issue, to help the NFL understand how these hits can affect players. He feels very strongly about this and hopes the NFL will create better pensions and overall healthcare for current and retired players.

“At some point you become retired, and it’s all about the benefits,” says Toi Cook, former cornerback for the New Orleans Saints. “Most players’ don’t have 12-year careers … when I retired you got two years of health insurance, I think it’s up to five now.”

Steinberg hopes to get the NFL to extend player benefits, provide better healthcare, give baseline tests, provide EKGs for heart monitoring and help these players live past the age of 55.

“Dealing with the injuries that occur in violent sports like football, every Sunday night during football season seems like an episode of ‘ER’,” Steinberg says. “[The NFL has to] take care of veteran retired players that made the game … they need to prioritize these health issues.”

Sports: Football

The Truth Behind Sports Concussions

By Elisa Hernandez

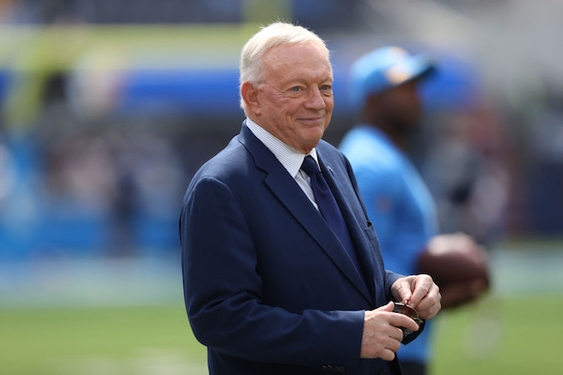

Troy Aikman suffered multiple conscussions when he played QB for the Cowboys in the NFL.

(Credit: PAUL MOSELEY/FORT WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM (DALLAS OUT)/MCT.)

Article posted on 8/3/2011

This article has been viewed 4274 times.