The museum’s founder, David Wilson has said that the MJT is a natural history museum, which focuses on presenting technological phenomena mostly gathered from the Lower Jurassic – phenomena so obscure that they might have otherwise escaped public notice.

But nowhere in the museum would you be able to find this clear of a description.

Instead, upon paying a voluntary donation of $5, you can watch an elaborate introduction: the tale of museums of antiquity, Noah’s Ark, 16th and 17th century wunderkammen or “wonder-cabinets” that were privately owned collections of unusual relics available to the general public. Essentially, the even-toned voice tells you, the MJT “preserves something of the flavor of its roots in the early days of the natural history museum.”

On the whole, this introduction elicits reactions of either interested confusion or discomfort. And it becomes even more curious: the museum is a rabbit hole, a dark labyrinth.

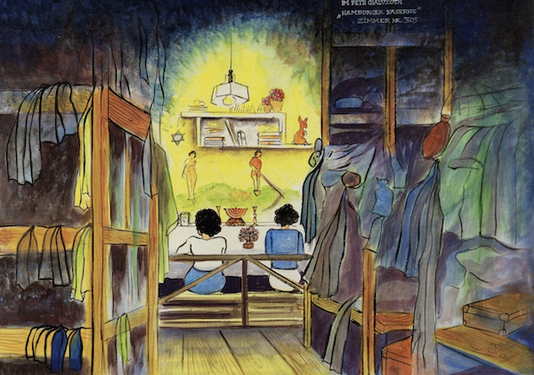

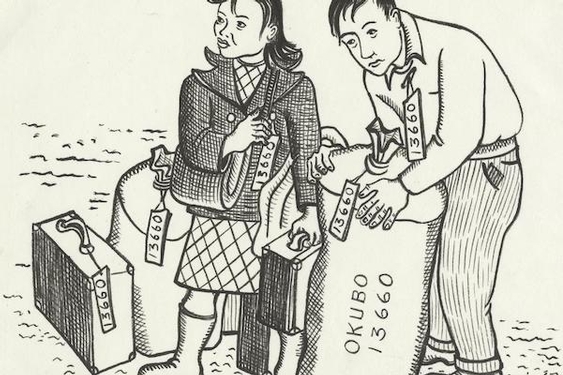

Exhibits enter one’s view bearing unnerving historical artifacts (a human horn), representational dioramas (a Cameroonian bat stuck in a mass of lead), double mirrors and holograms (Athanasius Kircher’s study of magnetism), all arranged in an unknown order.

The elusiveness that can frustrate some of MJT’s visitors is exactly what captivated me. At the MJT, one not only has the agency to decide what kind of museum it is, but what the exhibits mean at all. Or if they are even real.

Take the display of microminiature art by Hagop Sandaldjian; an accomplished violinist, who would painstakingly construct all sorts of icons out of dust, lint and hair onto a lone needle. I had read about this before, but upon looking through the high-powered microscope to find a tiny figure of Pope John Paul II in the eye of a needle, I was shocked.

That cross that the Pope held in his outstretched hand was made of dust? It just didn’t seem plausible.

But what did it matter if it was or not? The beauty of a visit to the MJT lay in our ability to question the truth of the exhibits, which rids our passive role as visitor and challenges our perceptions about the role of the museum in general. I recommend this place to anyone who has ever desired innovation, even collaboration from a museum of natural history.

For more information, visit www.mjt.org.